Vibe:

Like a Brontë novel come to life, "The Piano" is dark, Gothic romance at its best. It's a quiet, intensely emotional film, where everything is depressing and beautiful at the same time. As with many Jane Campion projects, it makes me want to immediately plan a trip to New Zealand.

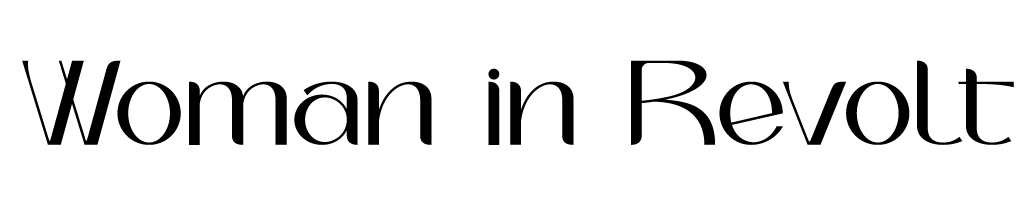

"The Piano" is also incredibly mysterious. Ada (Holly Hunter) has been mute by choice since the age of six. She communicates either by using a primitive form of sign language her daughter Flora (Anna Paquin) can interpret, or writing things down on small slips of paper she keeps in a silver locket around her neck.

Ada is stoic as hell and virtually unreadable based on expression alone. It's clear that she has a constantly running interior monologue, but the audience is only privy to that during the rare voiceover (where we're reminded that what we hear is the voice of her mind, not her actual speaking voice).

Best time to watch:

Now! It's the 70th anniversary of the Cannes Film Festival and "The Piano" is the only film directed by a woman to have won the Palme d'Or. And not to be a downer, but it technically shares the top prize with Chen Kaige's "Farewell My Concubine" (1992). If you're interested in a comparison of the two films, check out this piece by A.A. Dowd over at The A.V. Club.

Cannes historically doesn't care about female filmmakers (they've been shitting on Claire Denis for years), so it's interesting to rewatch this film and think about why it might have resonated with the jury in 1993.

You should also watch this film if you want to see Harvey Keitel's dick. I didn't particularly want to see it, but I always appreciate it when dudes go full-frontal (for equality, dammit).

Worst time to watch:

When you don't have the patience to watch 2 hours of Holly Hunter's silent, restrained passion and Anna Paquin's precocious little troublemaker schtick. Both performances are absolutely top-notch, but if you're not in the right mindset, their talent might slip by unnoticed or even become unbearably grating.

I watched this movie for the 5th or 6th time over the weekend, having just gotten back from 5 days of work in NYC. I probably should have watched something else, because I found myself supremely annoyed with every character when in previous watches, I hadn't felt this way at all. When Ada plunged into the sea with her piano, I wanted her to sink to the bottom and die a watery death. (Which is, coincidentally, how Jane Campion says she wanted the film to end).

Where to watch:

Google Play or iTunes.

Quick summary:

Ada, mute since the age of six, is sent away to New Zealand with her daughter, Flora, to marry a man she's never met. It's 1852 and Ada's father has sold her to the highest bidder, a weird loser named Alisdair (Sam Neill). They immediately get off on the wrong foot when Alisdair refuses to let Ada keep her piano, an object she cares for deeply.

George Baines (Harvey Keitel), Alisdair's friend, offers to take the piano in exchange for a piece of land and lessons from Ada. Alisdair agrees to this exchange because in addition to being a weird loser, he's also a moron. Ada and George start fucking, Alisdair finds out, and he chops off Ada's finger.

Oh, sorry... Did I ruin it for you? SPOILER ALERT. But really, this movie is from 1993 and there's not much to spoil. If you're watching a movie like "The Piano" in hopes of crazy plot twists, you're in for a disappointment.

Thoughts:

"The Piano" is delightfully bizarre and I'm happy that it won the Palme d'Or, but it's probably my least favorite Campion film. Unlike "Farewell My Concubine," the film it tied with at Cannes, the content of "The Piano" isn't necessarily important in the grand scheme of things. "Farewell My Concubine" is a politically significant film, but not exactly expertly crafted; "The Piano" is expertly crafted and worth watching for the acting and execution alone, but not politically or culturally significant.

Jane Campion is a far more talented director than writer and I prefer the projects where she works with Gerald Lee (like "Top of the Lake" and "Sweetie"). "The Piano" is a directorial masterpiece, which makes the screenplay look even weaker in comparison. Most of the characters are simplistically written and rely solely on the strength of the actors to add shading and emotional depth.

The way Campion uses the Maori people is also problematic. I understand why she included them, but I kind of wish she had left them out completely. During the period when the film takes place, New Zealand was being colonized by the English, and the interactions between settlers and indigenous people were certainly not as chummy as Campion portrays them (they were brutally violent).

It's obvious that Campion took liberties with history when writing the screenplay, but this rose-colored glasses approach to colonialism is too egregious to be ignored. If you want to read more, this scholarly article is excellent.

So if this film has a weak screenplay and ignorant portrayal of indigenous people, why do I like it? Mainly because of the stunning visual language. From the moment when Ada uses her hoop skirt as a makeshift tent on the beach, it's obvious that this is a special film. Each shot is perfectly composed and there are many that I think about often:

I would also argue that this is a feminist film with a strong-willed, badass central character. Bell Hooks, and many other feminist scholars disagree with me. Referencing the film after Alisdair chops off Ada's finger, Hooks notes,

Ultimately, the film suggests Stewart's rage was only an expression of irrational sexual jealousy, that he comes to his senses and is able to see "reason." In keeping with male exchange of women, he gives Ada and Flora to Baines. They leave the wilderness. On the voyage home Ada demands that her piano be thrown overboard because it is "soiled," tainted with horrible memories. Surrendering it she lets go of her longing to display passion through artistic expression. A nuclear family now, Baines, Ada, and Flora resettle and live happily-ever-after. Suddenly, patriarchal order is restored. Ada becomes a modest wife, wearing a veil over her mouth so that no one will see her lips struggling to speak words. Flora has no memory of trauma and is a happy child turning somersaults. Baines is in charge, even making Ada a new finger.

While this is an entirely valid read, I interpreted the film's epilogue differently. When Ada orders the men to throw her piano overboard, she's letting go of her obsession and darkness. It's dangerous and unhealthy, even in the 19th century, to rely solely on a piano to act as a voice and outlet for self-expression. If Ada continued to stay silent and let her music speak for her, how often would she be misinterpreted? Would she ever progress as a human being if she continued to practice complete restraint everywhere in her life aside from her music?

Artists can't and shouldn't live in vacuums. The best, most affecting art exists in conjunction with and in acknowledgement of reality, at least to a certain extent. Without forcing herself to let go of her old method of communication, Ada would have been a static character with no hope for happiness or deep human connection. I didn't read the ending as "patriarchal order restored," but as progress. Ada's voiceover tells us,

There is a silence where hath been no sound

There is a silence where no sound may be

In the cold grave, under the deep deep sea.

There's plenty of time for silence in death, but Ada is still alive and as much as she might not want to, needs to learn to use her own voice to express her thoughts and desires.