Quick summary:

Told non-linearly, Mascha Schilinski's second feature, "Sound of Falling," observes the occupants of a farmhouse in Germany's Altmark region during four different time periods: pre-WWI, the end of WWII, the 1980s, and present day. While some characters appear in multiple timelines, the unifying force is undoubtedly violence and trauma.

Vibe:

Bleak. Between the suicides, "work accidents," rape/incest, and all-consuming sound design that makes you feel like you've been conked in the head, you will emerge from this movie emotionally depleted. I can think of a few humorous moments throughout, but they were so laced with impending dread that I never so much as chortled. There's a scene toward the beginning where the sisters in the earliest timeline nail the maid Berta's (Bärbel Schwarz) shoes to the floor. When she slips them on and faceplants with the first attempted step, the girls break into laughter. It seems like a cruel, albeit relatively harmless, joke until Berta remains there, unmoving, for just long enough to stoke panic over potential injury. Eventually, she pops up and chases them, but it's unclear if she's angry or fooling around. The handheld camera and sound design add to the uncertainty, making Berta's intentions even more opaque as she chases the girls through the house's windy, dim passages as they scream with pleasure or panic. Even when something seems lighthearted, there's always a sense that it's temporary and darkness lurks just around the corner.

Reminiscent of:

"Sound of Falling" is a taxing, 2.5 hour-long contemplation on life's meaningless cruelty. It reminds me of movies by filmmakers like Ingmar Bergman, Joachim Trier, Lynne Ramsay, and Michael Haneke. Specifically, I kept thinking about Sofia Coppola's "The Virgin Suicides," David Lynch's "Fire Walk with Me," and Trier's "Sentimental Value" and "Louder Than Bombs." In Alex Heeney's podcast episode, which features an interview with Schilinski, she refers to this type of film as a modern gothic, noting,

They're not necessarily about a spooky mansion, they're not necessarily horror even if they're perhaps inspired by horror, but they are films where the location is a really important part of the story, and for many of them, the location is also associated with a site of trauma.

If this type of film appeals to you, "Sound of Falling" is easily one of the genre's strongest.

Best time to watch:

On a cold winter night when the snow is falling outside, a fire's roaring inside, and you think to yourself, "You know what would make this better? Watching a man's parents dismember him so he doesn't have to go to war." I was feeling pretty down when I saw this movie and was grateful for the lengthy distraction. Yes, the world still sucks in 2026, especially for women, but at least I can't be forcibly sterilized by my employer so they can rape me at will without the threat of lost labor when I inevitably fall pregnant. That's progress! (The depressing flipside is that in the present day United States, we're forcing people to have children future wage slaves they don't want/can't afford by criminalizing abortion.) This movie is a reminder that things could be worse in different ways, like the cinematic equivalent of being told to eat your meatloaf because there are starving kids in Africa.

Worst time to watch:

I wouldn't watch it in the throes of suicidal ideation or during a perfect day where my mood is so amazing that I question my clinical depression. Otherwise, any time is fine.

Where to watch:

If it's playing at a theater near you, go see it ASAP. It will stream later this year on Mubi, although a date has not been announced as of yet.

Thoughts:

This section is full of spoilers, so proceed at your own risk.

"Sound of Falling" is a movie about seeing and being seen, whether through the crack of a door, from a faraway window, or via reflection in a mirror. Someone is always watching and the identity of that person shifts, often so subtly that it goes unnoticed during a first viewing. Between the changing perspectives and timelines, it's a film that forces attention from the viewer even when the pace feels excruciatingly slow. As the credits rolled during my screening at IFC, I wasn't left thinking about any particular plot development or character, but of striking repeated images: an open-mouthed eel, a darkened tunnel of hay, smooth stones resting atop eyes, bare navels, pinched hands. Schilinski excels at creating disconcerting images that harken back to hazy memories of their previous usage in a way that mimics real life. It's a feeling of having seen something before but being unable to explain why it creates a sense of unease.

In the earliest timeline, a seven-year-old girl named Alma (Hanna Heckt) is our conduit to the farmhouse happenings. She's the perfect height to peer through a keyhole, watching intently as her amputee older brother, Fritz (Filip Schnack), gets a sponge bath — and later, a handjob — from Trudi (Luzia Oppermann), another one of the family's maids. It takes a while to get there, but Schilinski eventually shows us the day Fritz's "accident" occurred, another time when Alma saw something she shouldn't have. As she and her great-grandmother Frieda (Liane Düsterhöft) sit by the window, pitting plums, Fritz's parents drag him across the lawn into the barn. The other siblings watch from afar whereas Alma runs outside, pressing her face up to the crack between the barn's wooden slats to watch what ends up being a failed dismemberment (arm), followed by a shove from the hayloft onto the threshing floor. Fritz's injury from the fall is so severe that his parents get their wish: his leg is amputated, rendering him unfit for military service.

In subsequent scenes, it's impossible to see the barn without remembering the violence it harbored during his maiming. There's a repeated scene where Alma runs through a tunnel of hay, chasing another child. Much like the early chase scene with Berta, a menacing presence seems to clip at her heels. In one of these repetitions, she ends up on the threshing floor where the little boy she was once chasing is now lying dead in a coffin (and where Fritz once laid with his leg bent at an excruciating angle). We've also seen this boy in previous images at the beginning of the film. All we know about him is that a fly crawled into his mouth and the children are desperate to see if it's still alive inside of him. Once they tire of this, someone starts a game where the last one to exit the barn gets pulled "into the realm of the dead." Lia (Greta Krämer), the straggler, pranks the children by pretending she can't leave; a few months later, everyone takes post-mortem photos with her corpse.

There are many necrophagous insects, including several species of flies. That fucker is definitely laying eggs is this boy's cavities.

Alma is surrounded by death. On All Soul's Day, she sees a photo of a deceased older sister she never knew existed and is struck with a bout of morbid curiosity when she realizes they're wearing the same dress. Lia tells her this girl was also named Alma and died at age seven. The other sisters joke that maybe Alma is not herself, but this other, dead predecessor. Throughout the film, Alma is haunted by her ghost self, Fritz's missing leg, her great-grandmother Frieda who eventually dies on her way to the toilet, and Lia, who kills herself to avoid a lifetime of rape and abuse at the hands of her employer. Before Lia's suicide, the film gives insight into her perspective with voiceovers detailing the indignity of Frieda's death, with her ass exposed for all to see, and the poor treatment of the family's maids, who are sexually abused, in part because their forced sterility removes one major deterrent.

Lia is older than Alma and has a more advanced understanding of the horrors that potentially await; she foresees her fate before it's even solidified. In a brutal parallel to Fritz, she's sent away to work as a maid at a neighboring farm. The family gets into some kind of financial trouble and the parents essentially trade her for enough grain to get through the season. Lia is well aware of the life she's being forced into and, as Alma's voiceover tells us, nearly dies during her own pre-employment sterilization. When Alma sees her in the neighbor's field, sitting on a hay bale in the back of a wagon, she waves, they lock eyes, and Lia thrusts herself into the vehicle's path, embracing a harrowing death by crushing. Through Alma, we see the stripping away of childhood innocence as the viciousness of the world presents itself. All hay bales lead to death and destruction; all trauma begets trauma.

Non-linear timelines are tricky because when done wrong, the viewer obsesses over trying to properly orient themselves. Is it the 1910s or 1940s? Have we seen this image or person before? Wait, how are these people related? Schilinski offers no delineation between the timelines aside from the obvious — characters, wardrobe — and when those markers are missing from a shot, it can be difficult to place accordingly. Even within each distinct timeline, events don't necessarily happen in succession. Early in the film, we see a close-up shot of an eel with its mouth wrapped around someone's purlicue. The significance of that image isn't revealed until much later but we see it spliced into various timelines, just like the tunnel of hay. It's unfamiliar at first, becomes familiar with repetition, and delivers a significant gut punch when its origin is revealed. As those instances stack up — where Schilinski presents something out of context and then later provides it — viewers learn to embrace ambiguity in the moment with trust that clarity is imminent.

With the eels, Schilinski ties together the 1940s and 1980s timelines. In the 1940s, the briefest segment, a teen girl named Erika (Lea Drinda) obsesses over her disabled Uncle Fritz, sneaking into his bedroom when he's asleep, dipping her finger into his moist navel, and tasting it. Much like Alma, who could be her aunt or possibly her mother, Erika loves to spy on people. While watching her scenes, you feel aligned with her and assume the perspective being shown is her own. In reality, Erika's scenes are her sister Irm's (Claudia Geisler-Bading) memories. In the 1980s timeline, Irm and her family are living in the same farmhouse. Erika is dead, having drowned herself in the river with a group of women when WWII ended to avoid rape by Soviet soldiers. Irm also attempted suicide, but bailed when the eels began nipping at her feet. In the 1980s timeline, which is told primarily from her teen daughter Angelika's (Lena Urzendowsky) POV, Irm still harbors guilt/shame over her cowardice.

During a family party, everyone plays a game that involves riding a bicycle past a vat of eels, grabbing one with a single hand, and tossing it onto salt. When it's Irm's turn, she halfheartedly tries, and fails, clearly uncomfortable with everyone watching her body in motion: large breasts jiggling, hand clumsily grasping. It doesn't seem like a stretch to at least consider that she was raped after she failed to commit suicide in the '40s. In the '80s, there's a good chance that Angelika is being sexually abused by her uncle, Uwe (Konstantin Lindhorst). At the very least, both Uwe and his son, Rainer (Florian Geißelmann), Angelika's cousin, inappropriately ogle her, which she is aware of and exploits when it suits her needs. Whether Irm notices this and ignores it or doesn't see it at all is ambiguous, but it does seem like both of Angelika's parents are, in typical '80s fashion, hands-off in their parenting approach. Neither of them clock her suicidal ideations or increasingly risky behavior. We get no insight into how they feel when she disappears, although Rainer's voiceover tells us that no one talked about her at home and he never saw her again, to the point where he began to imagine she was just in his head.

One choice the film makes that I dislike is including Rainer's observations as part of Angelika's story. He's an insecure creep who sneaks into her room so he can catch a glimpse of her topless before accusing her of enthusiastic incest. We don't need insight into his thought process; everyone has met at least one teen boy like this during their lifetime and they're all the same. Seeing Angelika through his gaze adds nothing. He doesn't understand what she's going through, that she wants to engulf the barn/herself in flames when her cigarette hits the hay. He sees her as the '80s equivalent of a manic pixie dream girl, dancing in front of the mirror in her underwear and making fun of his boner. Instead, I would have liked to see Irm's version of Angelika. What does she see when she looks at her daughter? Does she realize a few eel chomps probably won't deter her from the river? If Irm wasn't so wrapped up in the trauma of Erika's death, maybe she would see that history is about to repeat itself.

Irm and Angelika don't feel like mother and daughter because there's no strong connection: both are isolated in their own separate worlds of pain.

Eels, the barn's dreaded threshing floor, and the threat of sexual assault also appear in the 2020s timeline. In this iteration of the story, a family of four is renovating the farmhouse: Christa (Luise Heyer), her husband Hannes (Lucas Prisor), and their daughters Lenka (Laeni Geiseler) and Nelly (Zoë Baier). The screenplay describes Christa as Angelika's daughter, although there's no indication of this in the film. For all we know, Christa isn't aware of her mother's identity or even that she used to live in the farmhouse. When I first read this detail I imagined, based on pure speculation and fucked up genealogy, that '80s Angelika disappeared because she was pregnant with Uwe's child (Christa). Maybe she gave her up for adoption and either started a new life or killed herself. We'll never know/the film does not tell us, nor do we get any interiority from Christa.

Compared to any of the previous periods, the 2020s are less blatantly horrifying. The family seems to love each other, no one (that we know of) is being molested, all extremities are intact. Lenka, the older sister, struggles with typical preteen identity issues. She becomes obsessed with a neighbor girl, Kaya (Ninel Geiger), whose mom recently died, and the two spend their summer days paddleboarding, swimming, and having sleepovers. Nelly, who is only five, is sometimes excluded and feels left out, but those seem like normal sibling dynamics. Even Nelly's daydream/fantasy about causing a panic by rolling into the river doesn't feel out of the ordinary. When I was mad at my mom as a child, I used to think about how sad she would be if I ran away and never came home, got hit by a car, etc.

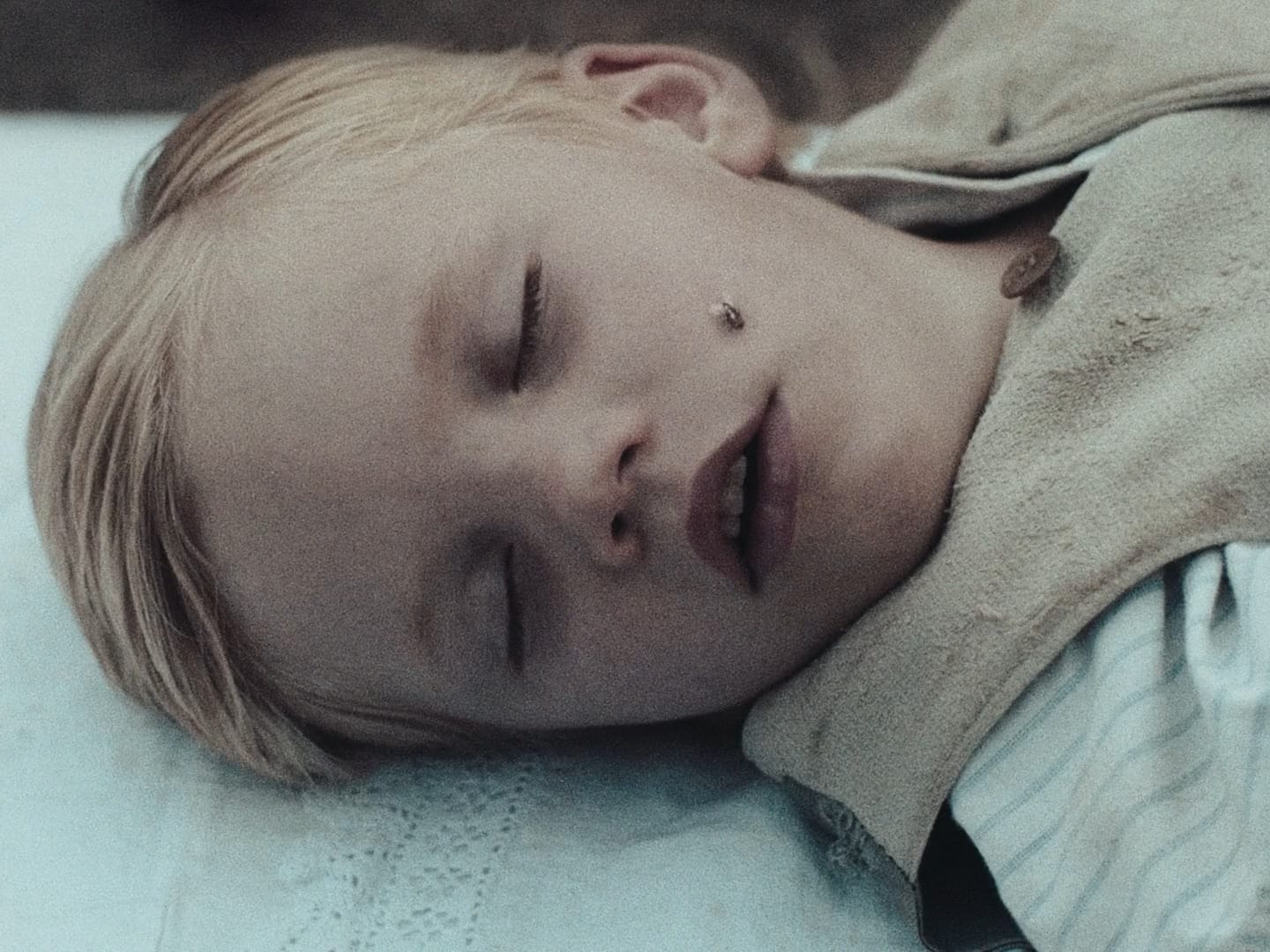

There are other threats of violence in this timeline, like when Lenka runs through the sprinklers topless and notices her parents' pervert friend staring or when she takes a stab at drowning with Kaya and is sent to the surface by a slithering eel. Nothing comes to fruition until the end when Nelly, seemingly unprompted, plummets from the top of the hayloft down to the threshing floor. Unlike Fritz, she isn't pushed; like Lia, she chooses to jump. Whether or not she understands the consequences of her actions is debatable. In the screenplay, she jumps because she thinks she can fly. The whole thing could have been another dream sequence if not for Lenka's voiceover from an older age, thinking back on the last time she saw Nelly and wishing she could remember more about that summer. Despite the occurrence of such a monumental event, all she can really remember is becoming friends with Kaya. To the viewer, Nelly's story feels incomplete, unknowable, because it is to Lenka and she's the one trying to tell it.

This is the section that reminded me most of "The Virgin Suicides." Kaya, Lenka, and Nelly: united by the pain of being a (teenage) girl.

In each period, tragedy strikes and time marches onward. People compartmentalize, repress, forget, fill in the blanks with fantasy and conjecture, tune out the pain and suffering around them... whatever it takes to create a palatable enough narrative to live with the weight of it all. When that doesn't work, they kill themselves. In the final image of the film, it's the 1910s and people are ducking behind hay bales as they get blown around by a "Wizard of Oz"-esque tornado. Lia gets picked up by the wind and floats, arms outstretched as chaos happens around her. When Alma joins her, the camera stays focused on their feet before the screen cuts to black. The moment before you hit the ground is euphoric and then it all ends.

Stray observations:

- So... Alma's dead sister is also named Alma? That makes sense because the parents in that timeline seem like the kind of freaks who would replace their dead kid with a 2.0 version just like those people who pick one dog name to reuse ad nauseam.

- The screenplay, which differs slightly from the film, is available here and definitely worth a read. There's a quote by Christa Wolf at the beginning in case you need further proof that Mascha Schilinski and co-writer Louise Peter are cool.

- After the year we've all had, I deeply relate to the 1910s mom (Susanne Wuest) who can't stop gagging.

- My favorite scene in the film is the one where Angelika daydreams about laying down next to the dead deer and getting run over by the combine.

- I just watched Schilinski's first feature, "Dark Blue Girl" (2017) about a seven-year-old struggling to understand her parents' divorce and subsequent reconciliation. There's a scene in the film where she dreams that her dad has been looking for her and, even though she makes her presence known by crying out and grabbing onto his shirt, pretends he can't find her. It instantly made me think of Alma up in the tree, screaming out for her sisters who leave her there into the night until Trudi rescues her.

- In case anyone else was desperate for this information, the book Christa reads at the river is Max Beckmann's "Drei graphische Folgen" (1989). There is no English translation, so I'm not even sure what it's about or when he wrote it. I primarily know him as a painter, a Weimar darling until the Nazis forced him into exile. Along with having ties to the 1940s timeline c/o fascism and the 1980s c/o pub date, he's also connected to the 1910s through WWI, where he served as a volunteer medic and was radicalized/traumatized. I found this review of his 2003 exhibit at MoMA interesting.

- The sound design, which I probably didn't talk about enough, is polarizing, but I do think it adds to the overwhelming foreboding feeling the film conjures so well. It's a staticky, windy, pulsing that reminds me of falling asleep on the couch and waking up to find the nightly broadcast had ended. (I'm technically too young to remember this but I've heard about it enough that I feel like I've experienced it. As Angelika says, "Memories are weird like that.")

- Character cross-overs: Fritz is seen (or mentioned) in the '10s, '40s, and '80s. Uwe and Irm in the '40s and '80s.