I am familiar with Annie Rose Malamet primarily through her subversive and controversial cinema podcast, "Girls, Guts, & Giallo." Each episode features a guest with in-depth discussion centered around a particular film, like "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre" (Hooper, 1974), "Rebecca" (Hitchcock, 1940), and "Antichrist" (von Trier, 2009). I wouldn't exactly call myself a horror person, but I do gravitate toward certain genre elements and always enjoy hearing takes from those who are more knowledgeable than me. Malamet comes at film criticism from a queer/kink/goth perspective, which is far too rare and incredibly informative. I learn so much by listening to her talk about film and really can't stress enough how much I enjoy her work.

There are certain films, especially in the exploitation and rape-revenge genre, that I tend to write off too quickly because I find them offensive. Malamet's criticism often helps me understand what certain people, especially women, might find interesting or worthwhile about these films. What's unsavory to me might have merit for someone else and as a critic, it's important to recognize and understand that. Even though I occasionally disagree with her analysis, I always find it thoughtfully considered and it often shifts my own perception.

If you're unfamiliar with Malamet, you're probably wondering at this point what exactly "lesbian vampire" means. To hear Malamet discuss it directly, I suggest listening to her talk at this year's Final Girls Berlin Film Festival, entitled "Her Hunger: The Lesbian Vampire & Queer Immortality, Suicidality, and Codependency." In this edited and condensed interview, we discuss lesbian vampire films, the rape-revenge genre, and the problems with "Promising Young Woman" (beware spoilers).

Interview with Annie Rose Malamet

Woman in Revolt: Give me an overview of your lecture topic for Final Girls Berlin.

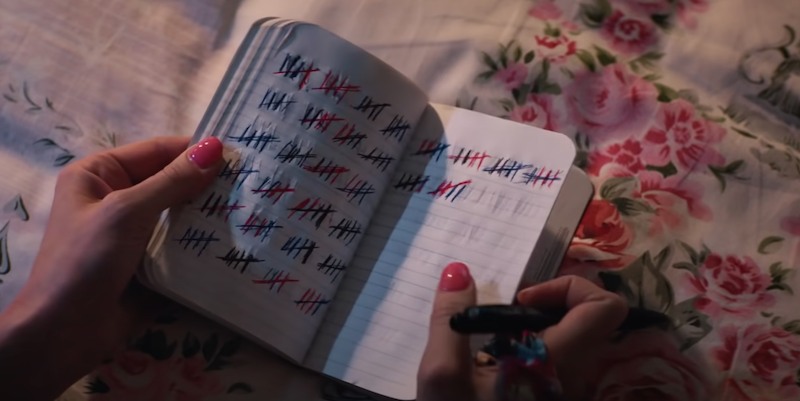

Annie Rose Malamet: The lecture is about the history of lesbian vampire films, but instead of a traditional linear history, it's looking at each decade and basically how lesbian vampire films as a genre can be used to discuss queer eroticism — particularly queer women eroticism — and co-dependency and suicidal ideation. All of the films across the decades explore these themes, starting in 1932 with "Dracula's Daughter." That's when you get the first existential, lonely, city-dwelling female vampire.

The scholarship has mainly focused on the way that these films utilize a male perspective because most of them (aside from a few recent films and one from the '70s called "The Velvet Vampire"[Rothman, 1971]) were created by men. Most of the discourse has been about how the lesbian vampire is a homophobic figure who perpetuates this idea of the outcast homosexual, the predatory homosexual. Then, there's the other school of thought, which is that the lesbian vampire can be reclaimed as a symbol of empowerment. I kind of take the track that all of these things are true at once, making it a lot more complicated. Do these films perpetuate the idea of the outcast homosexual predator? They absolutely do. But what's more interesting to me is how they are still very exemplary of these things that queer women struggle with that we seem to not be able to talk about in this age of assimilationism and queer pride.

I like what you've said about how all of these things, both good and bad, can be true simultaneously. Do you think the overarching impact of these films is dependent on the primary viewer?

The lesbian vampire as a figure is so enduring across decades. These films were originally supposed to be titillating, pornographic images for men, but the people who love and consume them are queer women. To me, the experience of the queer viewer is more interesting. That's step one toward dissecting why these films exist in the first place and why men made them. Going beyond that is the question of why they're so enduring. Why do people still like these films even though they're misogynistic? So yes, I do think it's dependent on the viewer and what they're bringing to the film. These images will resonant with queer people who have struggled with trauma, suicidal ideation, or not having a model for our relationships (and as a result, having toxic relationships).

You wrote a piece that I really like in Cultured Magazine that sort of dovetails with this. You said something about how immortality is inherently queer because it challenges patriarchal concepts. I had never thought about this before but it makes a lot of sense. Can you say more about it?

There's an academic paper where the author has touched on this in regards to the lesbian vampire and then I expounded on it in that essay. When your life could last forever, it kind of eliminates this patriarchal linear timeline that women have where it's like... you go through puberty, you mature, you get married, you have babies, you have grand babies, and then you die [laughs]. Outside of that, what could our lives be like if they were never-ending? If you don't have to worry about the clock ticking on whatever it is we're supposed to accomplish as women. If you're a woman who can give birth, are you going to have kids? If you're a trans woman, when are you getting the surgery? Time is running out. It's also inherently capitalist. If that [time constraint] didn't exist, what could a queer life look like?

And even if you shirk off the things that you're expected to do, there's still the burden that comes with going against society at large.

And that's really demonstrated in the figure of the lesbian vampire, who in being immortal, is outside of heteropatriarchal society and often struggles with suicidality... wanting to die or be free of this affliction. You could say that's homophobic, but it's also accurate and something that many queer people struggle with, which is more interesting to me.

In this case, it's more complex than saying "this is homphobic" or "this is not." Both ideas can be true simultaneously. I think the age that you get into something can also color how you read it over time. There are certain movies that I will always love even though I know they're problematic when viewed from a modern lens.

I wanted to mention that one of the origins of the lesbian vampire myth is the novella "Carmilla" (1872) by Sheridan Le Fanu, an Irish author. It predates "Dracula" (1897) by 26 years. Carmen Maria Machado, who is a queer woman author, did an intro for the book in 2018 (along with many footnotes) where she makes up this whole story about how Carmilla is based on a real woman who was executed for ... being a slut, basically, and having affairs with women. It's written in this way that makes you think, "Oh, wow ... she's done all this research and is adding to the book." But it's fiction. She inserts queer people back into the narrative, into this deeply homophobic lesbian vampire novella written by a man, but that queer people still love and cherish as part of the canon.

I haven't seen it, but isn't there also a recent film on Carmilla?

There are a few. There's the web series about Carmilla, which I haven't watched, and then there's the movie from 2019 directed by Emily Harris. The 2019 film is the most true adaptation of the book that I've seen so far.

Are there big differences that you notice between lesbian vampire films written/directed by women and those by men?

Yes, I do think there's a big difference. I was actually just writing another essay about this. Since men are not burdened by generations of raped and abused women in all of their choices and embodiments, they're kind of free to make really joyous, brazen, erotic, sadomasochistic work. I think women are struggling because they have to think about all of these things... like how it's going to fit into the discourse. You look at "Promising Young Woman" (2020) and how Emerald Fennell has to have a conversation with the history of rape-revenge films. I think that women directors feel that burden when they make lesbian vampire films. The films that are made by women are much less erotic.

"Carmilla" is not particularly interested in eroticism, it's interested in queer friendship and connection, discrimination, isolation, the patriarchy ... all of these things. The typical exploitation lesbian vampire film is not particularly concerned with that, it just happens to have it as a feature, which makes it really interesting. But to me, the other thing that makes it really interesting is the eroticism of it because I don't think that queer women are typically allowed — even when created by queer women — to be sexual beings. And not just sexual beings, but complicated and/or problematic. We're burdened with this idea that it has to be the perfect queer representation. I don't like perfect things; I like messy things. I think that's why I'm drawn in particular to these films. I want to see a woman make a lesbian vampire film that's messy and sexy in that way.

I didn't like "Promising Young Woman," but —

I didn't like it either, full disclosure.

[Laughs] Ok, good. But I will say that your comments about how limiting it can be for female creators and marginalized groups made me consider the film a little bit differently. To have the weight of so much history and scrutiny on your shoulders would be paralyzing.

Even with "Promising Young Woman," the conversations are so divisive. People have so many different opinions about it. There has definitely been discourse around men making rape-revenge movies in recent years, but I think that this movie in particular is getting so much spotlight because it was directed by a woman... it's a woman's rape-revenge film.

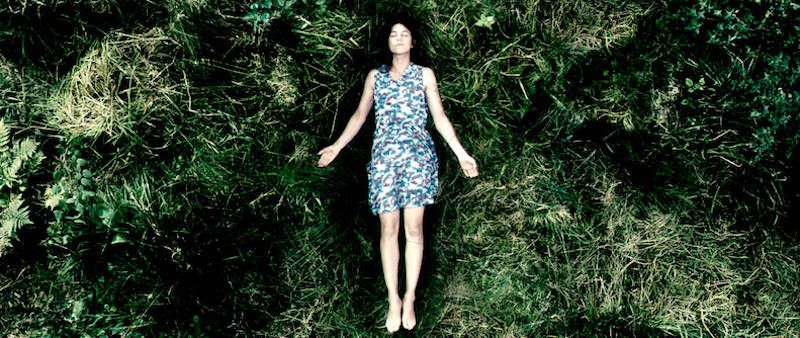

What's interesting to me is that there's not more discourse around the film "Revenge" (Fargeat, 2018), which was also directed by a woman.

I love that movie.

Me too. And the reason why I love that movie is because it is a traditional rape-revenge narrative but updated in a way that feels like a contemporary homage to the genre. What bothered me about "Promising Young Woman" is that the rape-revenge heroine is not supposed to die! And the police saving the day just doesn't feel right to me. The spirit of the exploitation rape-revenge film is that the protagonist is acting outside of the law, which has refused to help her.

Not that everybody needs to make the same movie over and over again, but I think that "Revenge" showed how effective updates could be made.

In "Revenge," we actually get violent catharsis at the end, which I feel is necessary. I like that we don't see the rape happen, though. That feels like an updated choice ... to avoid depicting it in gruesome detail the way that genre classics like "I Spit On Your Grave" have done.

And to that point, which I think ties into the lesbian vampire discourse, is ... what would it look like for a woman to depict a rape in a rape-revenge film? In "Revenge" and "Promising Young Woman," we don't see it. It's sort of accepted in feminist discourse that not showing it is somehow more feminist. But what would it look like? I would like to see it. Not to sound like a gigantic creep, but I just want to see how a woman would do that, just like I would like to see how a woman would portray a toxic, sexy lesbian vampire dynamic. Let's forget about men for a second and how they dictate all of our choices. What do we actually want to make?

That makes me think about this question of why women are drawn to horror. There can be something really powerful about seeing a thing that you're afraid of happening. I'm sensitive to depictions of rape on screen, but I am always interested in how women choose to handle it.

The example I'm thinking of is the French rape-revenge movie "Baise-moi" ( Despentes and Trinh Thi, 2000), which "A Promising Young Woman" was definitely inspired by. There are rape scenes in that film and it's directed by women. The French are always ahead of us.

I was trying to watch the movie "Bit" (Elmore, 2019), which is a newer lesbian vampire film and it was kind of rubbing me the same way as "A Promising Young Woman." It felt very corporate and kind of girl power-ish in the way it used that aesthetic. And with both movies, I feel like... if you're going to make the effort to have Black women on your cast, you should actually use them. In "A Promising Young Woman," Laverne Cox is essentially just the sassy Black friend, and that's terrible. I can't believe I haven't seen more of that in reviews.

That really bothered me. Why cast her of all people and then give her absolutely nothing to work with?

It was wild. The movie is very white... just the conceit that this Black trans woman would give a fuck about this white woman's love life at all. And also, the cop saved the day! The whiteness is the biggest problem with the film.

And not to harp on this film, but it just felt blatantly marketed toward women in a gross way. It ended with a pink wink face, for fuck's sake.

It's very post-Me Too, post-girl power. I felt the same way about "Bit," which has the lesbian vampires killing male rapists in some kind of revenge. Like oh god, can we just forget about men for like two seconds? It's frustrating.

Are there any themes that you wish more filmmakers would explore? It definitely seems like you want more provocative projects from female filmmakers.

I want women to have the space to make messy work that is advertent to the larger discourse but that muddles and complicates it.

I think that going into it and saying, "I'm going to create a feminist piece of art" is not the right approach.

What would we make if we weren't worried about that? That's what I'm interested in. I think "Revenge" does that in some ways. It's brutal and gory, which I love.

What kind of films did you like when you were growing up? And did you have a gateway horror film?

I was watching horror films from a young age because I grew up in one of those houses where my parents did not censor what I watched. The film that comes to mind first as a gateway is "Labyrinth" (Henson, 1986), with David Bowie. It's kind of a dark, gothic, creepy film. It made me interested in that kind of movie.

As I got older, I think the first horror film that I really clung to is "Carrie" (De Palma, 1976). The opening shower scene is so sapphic! Sissy Spacek's entire performance is incredible, Brian De Palma's directing... he's one of my favorite directors. Also, I was twelve and had just gotten my period, so it was extremely timely. "Carrie" is one of those films where the people behind it — Stephen King and Brian De Palma — are men, but managed to make a film that is beloved by women.

It's kind of weird when that happens.

There's something there! And I really think it's because they're not burdened by this shit. They can make whatever they want because they don't have to worry about... "Oh, am I making a patriarchal film?" They don't think about that, so they end up making very brazen, interesting work.

I've gotten more pessimistic with age, but I do hope that I live to experience a time when women aren't constricted by the worry of how their work is going to fit into the overarching feminist framework.

I would absolutely love that. I totally want to love movies made by women are always go into them that way. I wanted to love "Promising Young Woman." And of course, there are women making incredible work. I would like to see it more in horror and genre film in general.

Post-Me Too, there is so much heightened discourse around what is offensive versus what is challenging. I don't want to discount any of the Me Too wins but hope that after this period, we get more art that challenges mainstream ideas. And like you say, it might not always be perfect, but... chasing perfection can be paralyzing.

Because it's still so new for gay people to even be able to have public relationships (as sad as that is), we're not at the place where [messy art is accepted]. Take the movie "Adam" (Ernst, 2019), which I haven't seen and don't have an opinion on... the discourse was already stacked against it before it even came out because it's a messy story, written by queer people about something happening in the queer community [gender deception] that isn't savory. There's still so much pressure on us to make perfect representation. We cant yet say that actually, there are a ton of toxic dynamics in queer relationships.

That's a good way of putting it. It's like we're treating femininity or queerness as these perfect entities with no interior issues, which just isn't realistic.

I see tweets all the time that are just like... valorizing queer women as if they're safer than other people, which just isn't true. I have the luck and burden of having been out for a very, very long time at this point. I came out very young, so I've been out for about eighteen years. I've seen so many iterations of this. I'm not coming from a place where I've just emerged from the toxicity of the heterosexual community. I've been in the queer community for a long time and have moved beyond that and don't really care about it that much anymore. I care about what's happening to queer people.

What do you think needs to happen to get us to the place where the queer community isn't valorized and is allowed to be messy? Is it just a matter of more queer creators making messy work? Being open to engaging differently with ideas?

My answer is always going to be that there needs to be more queer people actually making things and not just like... Netflix churning out stuff where they had maybe two queer people in the writers' room. There are queer people who have interesting, complex ideas, they're just not getting the chances to make the work. Or, because of the streaming model, people's work gets put through the focus group meat grinder and what could have been interesting is destroyed.

There are also movies like "Ammonite" (Lee, 2020) that queer critics are tearing apart before they even see it because there's an intergenerational relationship, which is considered problematic. But if you watch the film, it's actually heavily symbolic and not about that. I think that's part of it... so not just queer creators not getting the chance, but the race to not be problematic. As much as that makes me sound like a boomer, I really do think that people need to engage with the work more thoroughly. Ask how it actually makes you feel instead of trying to hit buzzwords when you talk about it.

The other thing I think about is how the world of digital media is changing in a way that makes it so hard for people to make enough money to write thorough, engaging criticism. Everything I read pisses me off because it just feels like clickbait.

I've just been talking about this with my girlfriend, who is a film critic. Like... are these people actually watching the movie?! It feels clickbait-y or like they were watching it on their laptop at home while texting their friends.

It would not surprise me to find out that a lot of the popular film critics are just AI. It would make more sense to me if some of those reviews were generated by robots.

Do you know the writer David Ehrlich? I was reading some shitty thing he wrote about "In the Realm of the Senses" (Ōshima, 1976), which is one of my all-time favorite movies. It's terrible, fake SJW analysis that is so completely off the mark. I'm not saying that we excuse people because they were operating in a different time in history, but I'm just saying that they literally were in a different context and thinking about different issues. It's important to consider that.

The people who become popular rarely deserve it.

I know you primarily from your podcast, which I just got into during quarantine, so I'm still going through all of the back episodes. What made you want to start it?

I wanted to start it to share my perspective, which is that of someone who has been out for a very long time, has been a sex worker, am in the leather community. The reason I started it is because of all these things we're talking about. I felt like the discourse was stymied at this point of perfect representation and I wanted to disrupt that. I was listening to podcasts like "The Bechdel Cast," and I really respect the women that make that podcast but I just found the analysis so surface level and not queer-informed or sex worker-informed. Being from sex work and the leather community, my ideas of what is and isn't problematic are very different than other feminists.

I was just reading a book by Andrea Weiss that she wrote back in the '90s. There's a chapter on lesbian vampires where she equates sadomasochism with male desire, and I'm like... wow! People really think that. A lot of mainstream feminists think that because they're ignorant and not part of the community. I wanted to bring that perspective and I wanted something that was a rigorous analysis and not just two bros drinking beer and pandering. And also, I just like exploring the potential that film has to open up your imagination. As a femme-for-femme leatherdyke, I grew up having to piece together things from movies, music, and literature to create my identity. So I bring that perspective, too.

Are there any creators (not just in film) that you find inspiring these days?

I have to give a shoutout to Sarah Fonseca, who (in full disclosure) is my partner. She's doing really amazing work in film criticism that complicates the discourse. My other go-to is Monica Estrella Negra, who is the founder of the film collective Audre’s Revenge Film. It's a collective of Black Indigenous People of Color who make horror films. She's also a writer and filmmaker. Gretchen Felker-Martin, who is on Twitter @scumbelievable, is a trans woman, film critic, and horror author. I highly recommend her, as well.