In the slightly altered words of Michael Scott, "Well, happy birthday, America. Sorry your party's so lame." July 3 will go down as one of the saddest days in US history thanks to Cheeto's megabill that the spineless, sycophantic Republicans jammed through the House before the arbitrary July 4 deadline. If you thought things were bad before, buckle up because millions are poised to lose healthcare and ICE now has a larger budget than most countries' militaries. It's going to be a blast when citizens start getting deported en masse for criticizing the regime. But no, MAGA isn't a fascist/racist/misogynistic death cult. They want to help all Americans... of the white, male, billionaire variety.

If, like me, you plan to spend the weekend dissociating, proceed for some random yip yap. By the time you're reading this, I'll be diving into a pond in middle-of-nowhere Pennsylvania, thinking about all the disgusting things that live in ponds, thus ruining my pond swimming experience.

First, an update on my trip to the Emily Dickinson Museum: it was magic. I would have happily paid $20 just to stand in her bedroom, staring at the floral wallpaper, imagining her hunched over a tiny writing desk in the dead of night, thinking about death, as a candle flickers in its chamberstick. I sadly did not encounter any cats on the property, but I was pleased to learn that Lavinia's fondness for them harkens back to at least age 7. At first, this painting of the Dickinson children hanging in the parlor looks unremarkable. Like ok, cool, Emily loves to read, so she's holding a book. The frame hides an important secret, though. If you look closely at Lavinia's hand in the photo on the right, you'll see that she's holding a drawing of a little black cat.

These are adult heads and necks on child bodies. Was this some craniology bs?

When I got back from the museum, I was immediately tempted to buy "The Letters of Emily Dickinson," a giant tome of her many correspondences. Instead, I remembered my current lofty reading commitments ("Swann's Way," "2666") and began trolling the internet for a quick hit of sweet, sweet rabbit hole distraction. What I found is this great series in the Los Angeles Review of Books where Alexandra Socarides takes a poem that everyone thinks they know and flips it on its head. With Dickinson, most people either think of "'Hope' is the thing with feathers" or "I'm Nobody! Who are you?" The latter is especially deceptive. "Nobody" is often taught in middle school as an anthem of individuality, a way to make quiet kids feel at ease with themselves in a world full of attention seekers. As with most good poetry, a closer examination muddles any simplistic read by uncovering contradictions and uncertainty.

During her lifetime, Dickinson only published ten poems, all anonymously and basically against her will. She has a whole poem about how the practice of commodifying art grosses her out, and honestly, I get it. She didn't need the money and she didn't seem to want the fame, so where's the incentive? When she died, Lavinia discovered ~1,800 poems and enlisted Mabel Loomis Todd (give this bitch a Google) and Thomas Wentworth Higginson to prepare them for publication. This process was challenging because many of the poems contained variant words with vastly different meanings. What I love about Socarides's interpretation is how she uses these variants to explore Dickinson's thought process and open up our understanding of the poem.

"High Hopes" is about conjuring up enough optimism to get yourself and the people around you through the shitstorm of modern life, which is even more relevant in the wake of Trump. It's far from my favorite Mike Leigh, but it features one of my favorite film couples: Cyril (Philip Davis) and Shirley (Ruth Sheen), two Marxists who eschew the yuppie boom brought on by Margaret Thatcher. Cyril is a motorcycle messenger, delivering mail to all the office drones he hates. Shirley works as an arborist for the city. They spend their days earning what they need to survive and their nights mostly at home, stoned, in their rundown little flat, adorned with cacti and political posters.

The main source of conflict comes from Cyril's family. His mother, Mrs. Bender (Edna Doré), lives in one of the last remaining council houses in a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood. The wealthy couple next door are actively annoyed by her to the point of downright hostility, making no secret about their desire for her to vamoose. Cyril's sister, Valerie (Heather Tobias), is one of the deeply unhappy nouveau riche who is surrounded by fancy things, living a life of zero substance. The film is about how Cyril and Shirley navigate life with their principles/sanity intact amongst all the bullshit.

What makes their relationship so admirable is the respect they have for each other, especially in moments of disagreement. Cyril is more misanthropic than Shirley and is baffled by her desire for children, declaring, "no one gives a shit what sort of world kids are being born into." Shirley doesn't necessarily disagree, she's simply more hopeful about humanity and her ability to help alter its bleak trajectory. Under a lesser director, this conflict could become trite and moralistic, but that's not how Mike Leigh rolls. The film doesn't end with Shirley pregnant or with Cyril's newfound enthusiasm for a baby. The final scene is hopeful, just not in a way that ignores the harsh reality of financial fragility.

I knew I was going to like this essay based solely on its opening line:

A series of haphazard walking errands led to me wandering downtown, lugging a tub of CBD gummies, a multipack of ultra-absorbent tampons and a 10 lb biography of Sylvia Plath.

Alright, Patricia Lockwood... not only are on the same wavelength, it appears we are similarly inspired by/fascinated with Sylvia Plath. And really, who isn't? "The Collected Prose of Sylvia Plath" came out in 2024, giving Lockwood a good excuse for a deep dive through thousands of pages. "Prose" clocks in at 848 pages, followed by "The Unabridged Journals" (768) and "The Collected Poems" (384). A mere toe dip into the biographies and/or the Plath-Hughes relationship lure could have you easily tied up for years. Lockwood touches on most of it, cherry-picking the details she finds most interesting and enhancing them with wry commentary. Take, for instance, this passage:

Hughes spoke, after he had left Plath and their two children at Court Green, of Sylvia’s ‘particular death-ray quality’. It’s possible this is true. It’s also true that men say the most insane shit when they’re getting divorced.

Or this "stars — they're just like us!" description of Plath:

She was always having a big coffee idea of what to name a collection or one of her characters and it was always terrible; this is perhaps her most relatable aspect. That and her love of stews.

By the end of the essay, you'll have a renewed appreciation for Plath that is neither fawning nor overly critical, along with a burning desire to read more from Lockwood. Everybody wins except for Proust, who's probably getting pushed to the wayside yet again. [Adds "Priestdaddy" to library holds.]

In grad school, I was obsessed with the documentaries coming out of Harvard's Sensory Ethnography Lab (SEL), directed by Lucien Castaing-Taylor. The SEL describes itself as

an experimental laboratory that promotes innovative combinations of aesthetics and ethnography. It uses analog and digital media, installation, and performance, to explore the aesthetics and ontology of the natural and unnatural world. Harnessing perspectives drawn from the arts, the social and natural sciences, and the humanities, SEL encourages attention to the many dimensions of the world, both animate and inanimate, that may only with difficulty, if it all, be rendered with words.

What is the experience of watching films made by the SEL like? Imagine going to a museum and wandering into a video installation where you observe people or animals existing. A grouchy friend might watch it for five minutes before declaring, "This is about nothing!" and walking away in a huff, whereas a person with the ability to sit and truly observe is rewarded with humor and insight. "Sweetgrass," which Castaing-Taylor made with his partner, Ilisa Barbash, is a meditative, observational, 101-minute documentary about a flock of sheep in Montana. "That sounds boring as fuck," grouchy museum friend growls. Little does that imbecile know, he's missing out on one of the best breakdown scenes in cinematic history.

This film is for people who don't need exposition, voiceovers, or explicit details about anyone or anything. Watching it is like stepping through a portal and discovering a world where nature and humans are uneasily intertwined, maybe even one and the same. In an interview with Framework, Castaing-Taylor describes it like this:

In some way Sweetgrass does seek to anthropomorphize sheep, and simultaneously to bestialise humanity. I think [John] Dewey was dead right in his 1934 Art as Experience where he insisted that the best art recouples us with our base, bestial selves, and yokes culture back to nature, and the human to the live animal.

Amongst all the nonsense of modern life, this is a breath of [slightly menacing] fresh air.

I've been thinking a lot lately about what makes something comforting enough to become infinitely rewatchable. With the advent of streaming services, it's easier than ever to let "Gilmore Girls" play on a loop in the background while cleaning the house or completing a particularly mindless work task. Research has shown that watching familiar shows can "restore [...] feelings of self-control after a period of exertion.” Real life is scary and unpredictable, so it makes sense that in times of upheaval, people look for the calm reliability of Emily Gilmore's cuntiness or Carrie Bradshaw's narcissism. What I'm more curious about is which shows fall into this category and why?

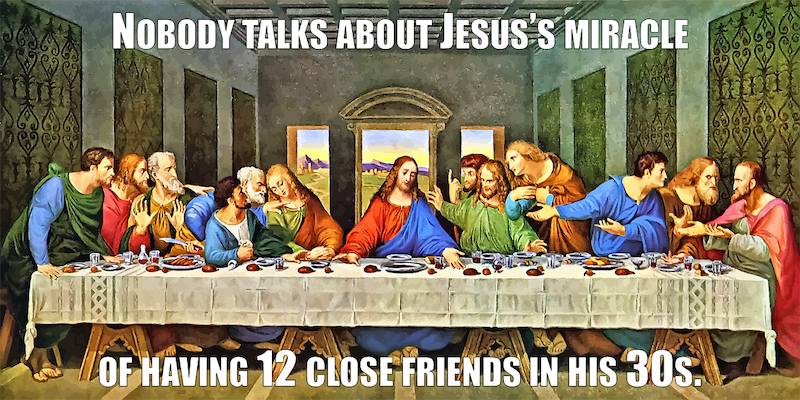

For me, there's definitely a strong nostalgia component to "Gilmore Girls" and "Sex and the City." When I first watched them, I was in a particularly hopeful place in my life. I didn't yet understand the world's cruelties and naively believed that if I just worked hard, the world would shower me with all the praise, love, and appreciation I deserved. With other shows, the rewatchability is more mysterious. "Younger" and "The Bold Type" aren't particularly good shows, and I watched both of them during a stressful time that I'm not keen to mentally revisit, so what's the appeal? It's probably the fantasy of an adult life full of friends who not only have the bandwidth for emotional support, but live close enough to be there physically. I'm not saying that all of my friends are garbage, but I've moved around a lot in my adult life and I don't live near (or like most) family, so daily existence is relatively isolated. I can't call a friend and expect them to spontaneously meet me for a coffee. I can barely get someone to accept an unplanned phone call. That's modern life, baby.

So as not to end on a totally downer note, here are some other comforting common denominators I've identified:

- When characters have a regular hangout — Luke's Diner, Central Perk, PJ Clarke's, Coffee Shop, Pip's Diner, Pop's Chock'lit Shoppe, etc.

- The rapport between two specific characters who seem to understand each other particularly well — Don and Peggy, Rory and Paris, Alicia and Kalinda (until it all went to shit)

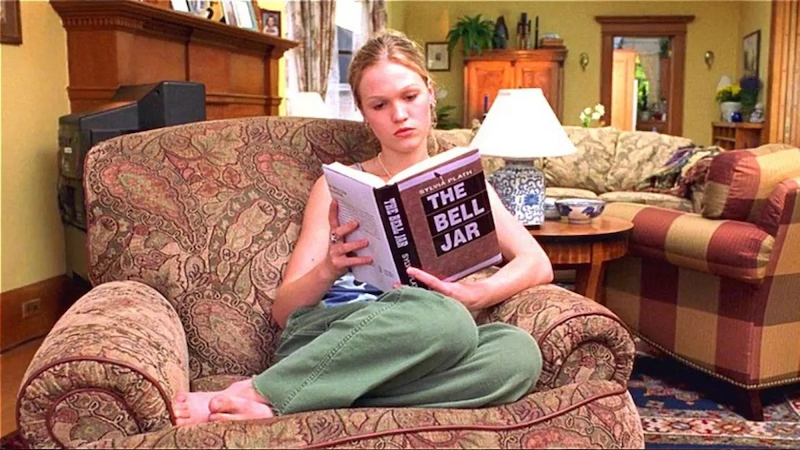

- A fantasy that'e so enticing, you're willing to completely suspend your disbelief in order to enjoy it, e.g. the aforementioned variation on this treasured meme:

Are you sufficiently cheered? I started strong and then slowly undermined myself, but at least I tried.

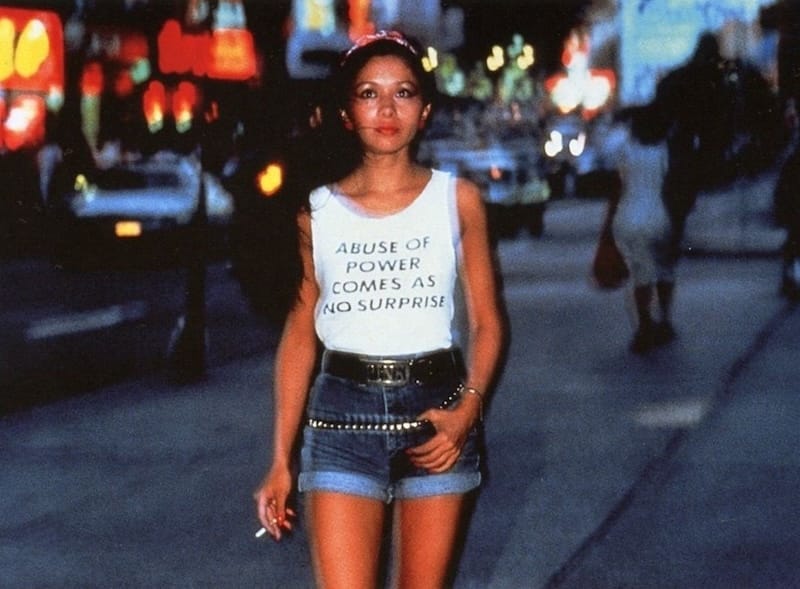

I leave you with Lisa Kahane's photo of Lady Pink in Times Square in 1983, wearing a Jenny Holzer "Truisms" tank and looking cool as fuck.